The loudness (vocal, gestural) of his character and performance means you can’t ignore him, and all the body grease and hieroglyphics, along with the perfectly fine Russki accent, only add to the distraction. Farrell is watchable and sometimes funny, if not especially menacing. As Valka, a gambler with a knife he calls Wolf, Mr. That isn’t his fault, but rather that of filmmakers who decided to cast a well-known Irish actor as a Russian gangster in an ostensibly true saga. (Bury your clothing in the snow.) The unspeakable conditions, the grime, haunted faces, violent outbursts and eerie lighting - along with the startling contrast between the splendor of the natural surroundings and the ugliness of the camp - makes this place of death come alive, a verisimilitude that’s almost undone when a heavily tattooed Colin Farrell starts throwing gangster attitude.

THE WAY BACK 2010 HOW TO

He harvests wood and digs for coal, learns to keep quiet and how to vanquish lice. Smith (Ed Harris, terse, tense and very Ed Harris), who warns of the dangers of kindness, Janusz settles into the prisoner’s routine. With the eager help of Khabarov (Mark Strong) and the rather more sharp advice from an enigmatic American, Mr.

Weir seems to think of her more like a beautiful, if harsh, mistress, an attitude that initially works to his film’s advantage, only to become an increasing liability.

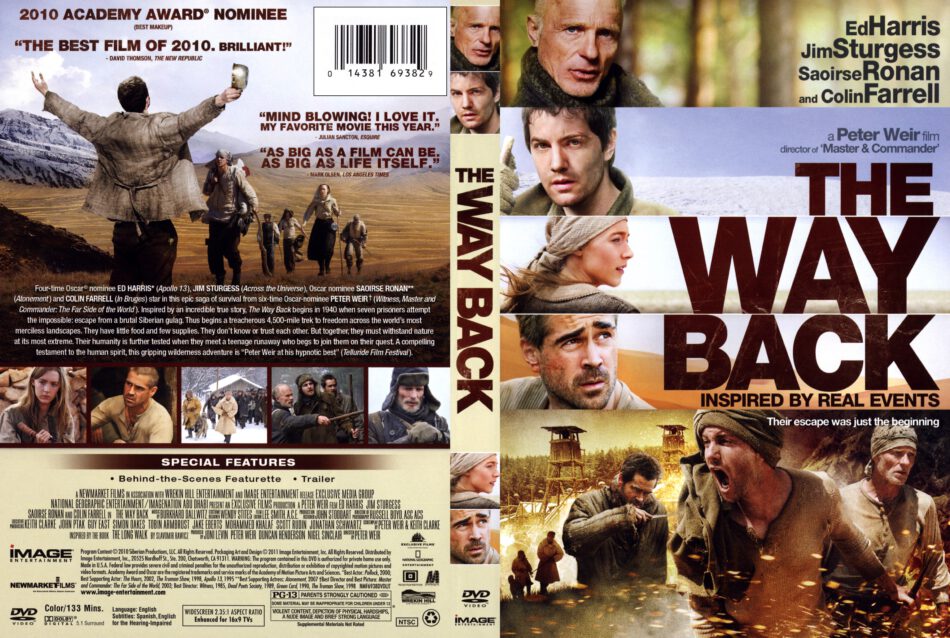

Cut to Siberia where, amid the haunting mountains and indigo light, a labor camp officer tells Janusz and hundreds of other accused enemies of the people that (in a somewhat Herzogian, as in Werner, pronouncement) “nature is your jailer, and she is without mercy.” From all the stunning landscapes, Mr. The film opens, in a short scene that’s a preview of the horrors to come, with a barking agent accusing a young Polish cavalry officer, Janusz (a very fine Jim Sturgess), of criticizing the Communist Party and spying for foreign powers. Surviving on moldering provisions and precious scraps of protein, dodging predators, two-legged and four-, the travelers embody a besieged humanity that might have been more stirring if their torment were in a rather less exquisite frame. For months a veritable league of national types, united by desperation and the English language, push through the cold and the heat, slipping through forests and across mountains and deserts. “The Way Back,” a heroically minded survival story from Peter Weir, tells the possibly true tale of a group of prisoners who fled a Soviet gulag in 1940 and walked, wandered and all but crawled to freedom.

0 kommentar(er)

0 kommentar(er)